__UPDATE: A previously published version of this story misidentified Roy Dawson's year of death. The Arrow regrets this error.__

Jim Hamby didn't follow the institutional rules or mandates that came with working in academia.

"He marched to his own drummer," Dr. Robert Hamblin, emeritus professor of English and assistant director of the Center for Faulkner Studies at Southeast Missouri State University, said.

Hamblin only recalled one time he and other colleagues even got remotely close to swaying Hamby. After some convincing, he finally turned in papers to be promoted from assistant professor to professor.

"Over in the service section, he listed that he served ice cream at the student come-back-to-school social. That was his service for the university," Hamblin said, smiling. "He just made a joke of the whole thing."

The 6-foot-4-inch, 250-pound man Hamblin described was the football coach from 1958 to 1968 and later a philosophy professor at what was then called Southeast Missouri State College. And students loved him.

"One of the most popular teachers on campus," Hamblin said.

But Hamblin added Hamby wasn't completely extroverted. His philosophical side actually made him more pensive in nature. So it didn't come as an overall surprise when he dropped golf for bird watching.

"Even when we were still playing golf together, he'd fall behind if he found a bird in a tree," Hamblin said. "We'd be putting on the green, and he'd be back down there looking at birds in the woods."

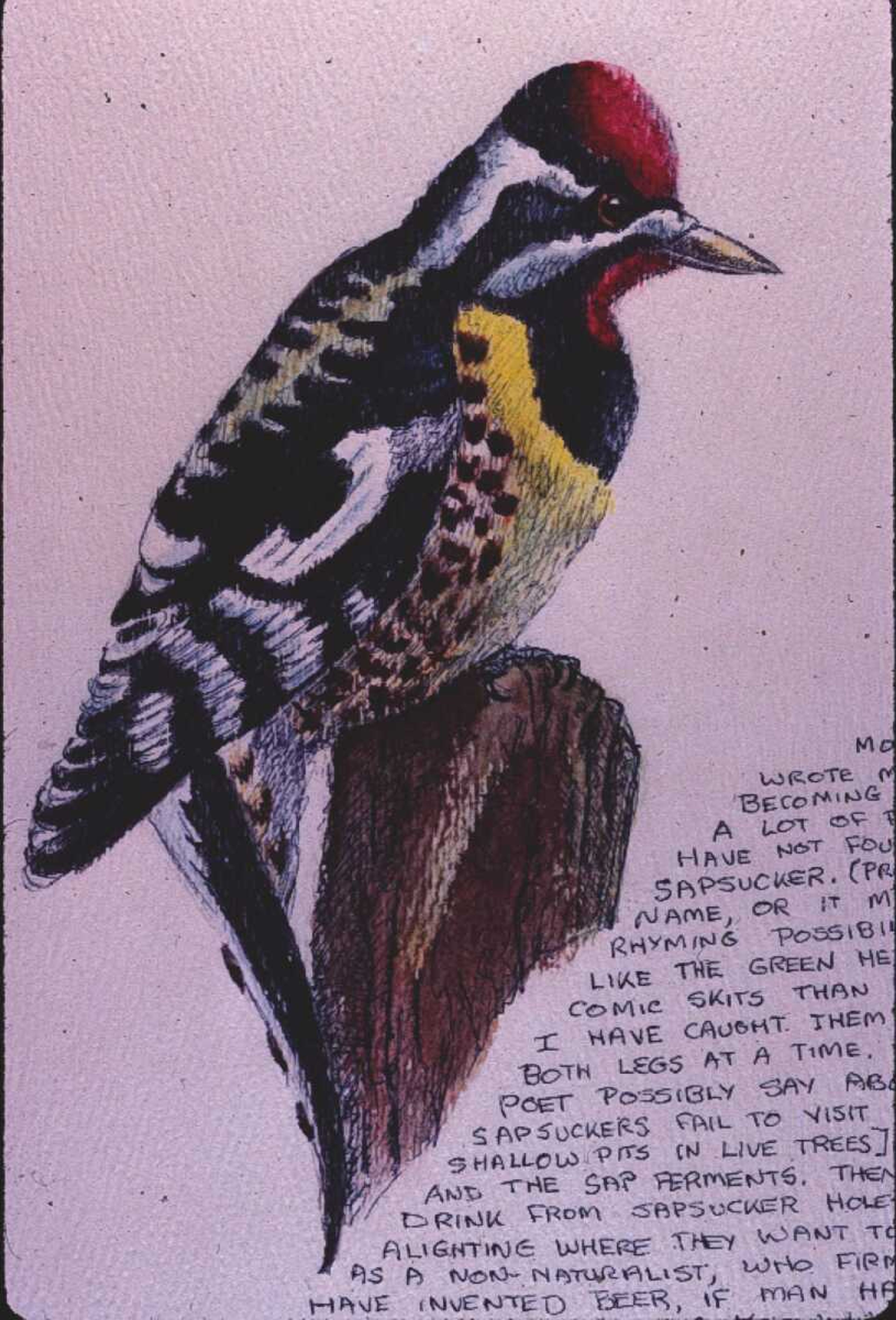

What he observed he recorded as drawings, primarily by using watercolor, with a piece of writing to correspond. These creations became gifts, going to students, colleagues, family and friends. Out of the estimated 300, around 200 have been found and archived at Southeast. Hamblin and Roxanne Dunn, Special Collections and Archives librarian, are working as co-editors to compile around 50 of Hamby's pieces into a book, which will be published by the University Press in the fall.

The writings underneath the drawings, artistically arranged in and of themselves, vary in topic. Hamby may write specifically to the person the drawing was intended for, or nostalgically -- a vignette of what could become a larger memoir.

Hamblin noted the drawings came first, so there was no room for edits in Hamby's process.

"It's kind of stream of consciousness writing," Hamblin said. "So he starts out just with a memory or a reflection or an impression, and then he writes until he gets to the bottom of the page."

While Hamblin tackles the transcription of the writing, Dunn is responsible for selecting the final drawings to be included in the finished book.

Dunn brings a different perspective to the table, never having met Hamby. Instead, she looks at a combination of what's aesthetically pleasing in the birds, but what's most relatable in the writing, too.

"I'm looking at it from an outsider's point of view, essentially," Dunn said. "And some of his things you can really relate to, and I think those are the birds I get drawn to a little bit more."

Yet Hamblin's memories of his friend are just as necessary.

"Because you can just read it on paper, but I can more imagine the tales that I hear about him and learn," Dunn said. "Then what I read, I can put together a better image of what he must have been like as a person in my head. So that combination is pretty rare for an archivist."

Hamblin said, like all artists, Hamby hoped for a book. Roy Dawson, former professor of English at Southeast, first started that project. Hamby didn't document who the drawings went to over the years, though, and died from a heart attack in 1986 not long after Dawson began trying to find them. Dawson was the one who tracked down the pieces and produced the color prints now archived. However, before he reached his end goal, Dawson died in 2009.

Hamblin and Dunn worked with Dawson's widow, Carol, to revive the project in 2015. She had held on to her late husband's files.

"I don't think Jim Hamby was ever really recognized or appreciated for being as great as he actually was," Hamblin said. "And when you start reading, this is some of the best writing. I read a lot, and this writing deserves to be out there."

Hamblin and Dunn hope to set up an exhibit in correlation with the book launch as well. Rather than running the presentation as editors, they want people who were gifted the drawings to read their affiliated passage.

"It's really what Hamby wrote for them, which makes it more special," Dunn said.

Hamby wasn't writing for promotion or tenure. He was writing to share with other people.

"Jim's ultimate subject was life, the human condition," Hamblin said. "And that's paradoxical because some days we laugh and some days we cry, and it's all in these writings, it's all in these birds."