On Aug. 24, a 6.2 magnitude earthquake hit central Italy killing an estimated 294 people and decimating mountainside towns. For two weeks, rescuers have been searching for those missing after tremors sent many ancient buildings toppling down.

This isn’t the first time an earthquake of this magnitude has hit central Italy. In 2009, a 5.8 magnitude earthquake also hit the region. Towns like L'Aquila, Italy, are still rebuilding seven years later.

Many buildings in central Italian cities affected by these quakes are thousands of years old, and most of them have not been retrofitted to survive a quake of this magnitude.

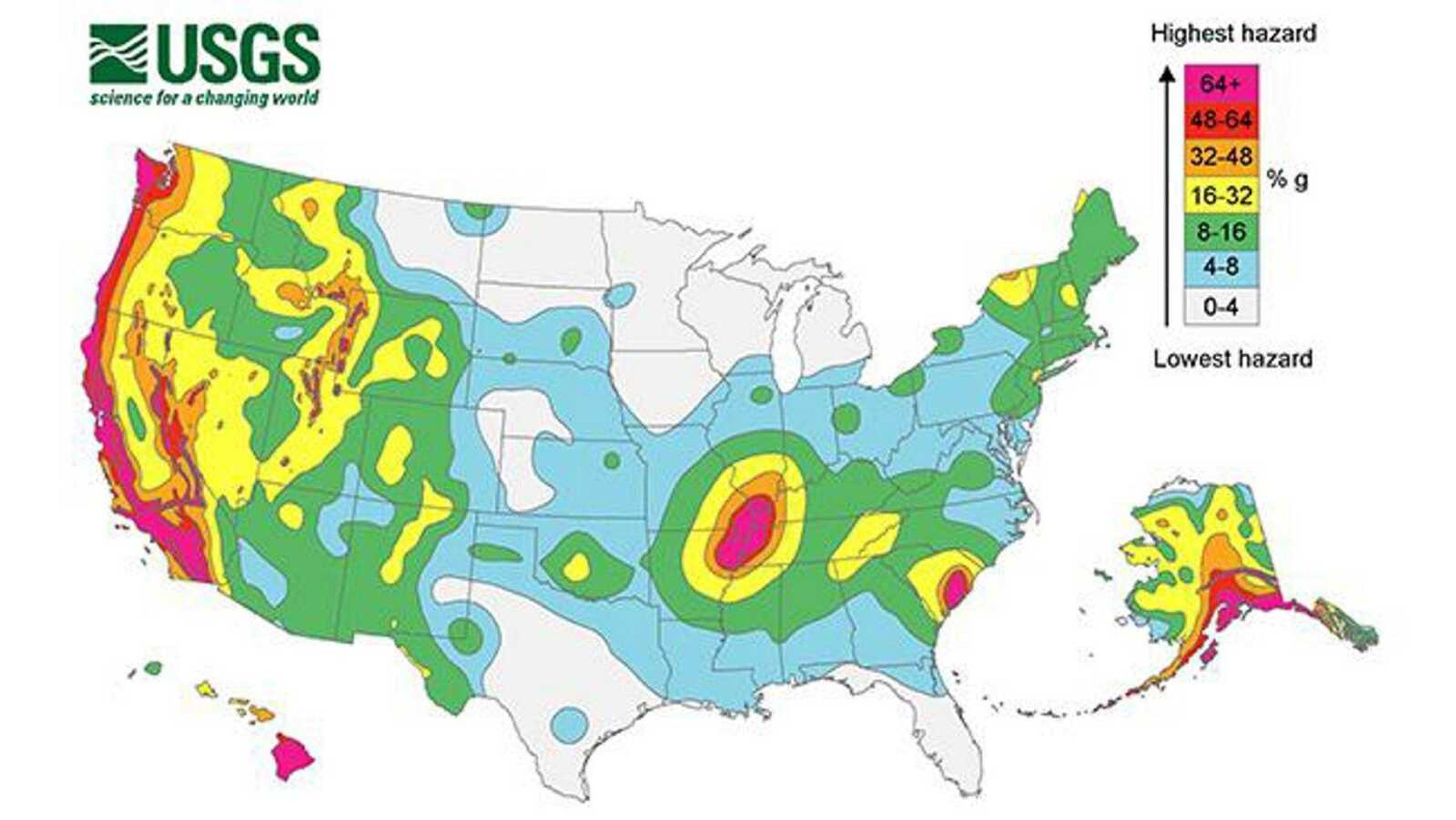

The occurrence of earthquakes in central Italy is lesser than in places like California or even Southeast Missouri.

Cape Girardeau and other towns in Missouri’s bootheel rest on what is called the New Madrid Fault Zone, which encompasses parts of northern Arkansas, western Tennessee, southern Illinois and part of Kentucky.

According to Katherine Perkins, a geologist who has worked with the United States Geological Survey, has done field work in Colorado, California and other states and is an instructor in the Department of Physics and Engineering Physics at Southeast MIssouri State University, this fault zone is caused by a 500 million-year-old failed rift system that is being pushed on all sides by other tectonic plates.

“A lot of people think that the New Madrid is one fault line, but it’s not, it’s a fault zone,” Perkins said. “Roughly 500 million years ago, in the continental crust, it tried to stretch apart. You can think of it in terms of little kids’ block. You have one here, here and here. When you start pulling them apart, one falls down. And that is the beginnings of a rift system.”

Perkins said the system died and never finished rifting. Over time, sediment buried on top of what is, essentially, a drop-down block of the Earth’s crust. Now, the North American Plate eastern boundary is pushed by the Mid Atlantic Spreading Center. Combined with the subduction on the western edge of the continent and pushing from the Caribbean Plate to the south, the mid-continental fault systems, such as the New Madrid, are under constant pressure.

“There’s a lot of other faults that are related to the New Madrid fault, which is why it’s a seismic zone,” Perkins said. “We have this old rift, now it’s being shoved, has a lot of stress added to it over time. This moves really slowly, about as fast as your fingernails grow. That rift is getting squeezed and adjustments must be made.”

Perkins added the Reelfoot Lake formed as part of this rift system. The Mississippi flowed into a down dropped block of crust and formed the lake.

The New Madrid Zone is made up of a number of different types of faults caused by different kinds of movement and pressure. Because of the constant movement, the New Madrid Zone experiences approximately 200 microquakes every year that are too small for the average person to notice.

In 1811 and 1812, the New Madrid Seismic Zone faced four 7 or 8 magnitude earthquakes that reportedly shook church bells as far away as Boston and caused the Mississippi River to flow backward.

Were an earthquake of that magnitude to hit the zone today, Perkins said Memphis, Tennessee, and bootheel communities would be heavily damaged. Even St. Louis would suffer major damage.

“Depending on the type of rock you’re on will determine how much shaking you actually feel,” Perkins said. “If you look at the bootheel, it’s all alluvium, floodplain and other loosely consolidated sediments that have a lot of water in it. With that water-saturated soil, you get that liquefaction, which essentially will shake like a bowl of Jell-O.”

A lot of homes in the southeastern Missouri area are built out of brick, which, according to Perkins, is effective against tornadoes, but not so much earthquakes.

“The harder and more brittle your building materials are, the more likely they are to crumble,” Perkins said.

Perkins said wood-framed homes have the ability to sway with the tremors. Structural damage is still likely, but there is a lesser chance of complete destruction depending on the area.

Perkins added that even though the chance of an 1811-like earthquake striking the area within the next 50 years is about 7 to 10 percent, people living in the area must still be prepared for the worst.

Southeast encourages all students — especially resident assistants — to attend Community Emergency Response Team (C.E.R.T.) training to prepare for natural disasters of all kinds. The training occurs once a year and is offered free of charge. The training consists of disaster preparedness, fire suppression, medical operations, light search and rescue and other disaster-related skills to help students and community members prepare and plan for natural disasters.

“If citizens are prepared their communities are prepared, and everything will run smoother in case there is a disaster,” Jim Watkins, the coordinator for C.E.R.T, said.

According to the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, being prepared for a natural disaster begins with having a plan. Students should have a plan in place that dictates where to go in case of an earthquake and how to get there. In some cases, your car might be a safe place to go following a disaster.

“We always recommend to students that, if at all possible, keep their gas tank at least half full,” Watkins said. “It’s shelter and it’s a way to get away from a disaster situation if possible.”

Students also should have an emergency kit that includes water, food, medical supplies, sturdy shoes and a change of clothes.

“It’s common sense things, but we really don’t think that way,” Watkins said. “We always think, ‘Well, I’m just going to my car. It’s 30 degrees out, I don’t need a coat.’ Yes, you do.”

If an earthquake occurs, Watkins advises students to be aware of their surroundings at all times. Students should watch out for falling power lines or fires. If students are inside, they should hide under something sturdy until it is safe to move outside, if it is safer to do so.

Earthquakes in southeastern Missouri are so infrequent that Watkins said many don’t think to prepare or train for disaster response, especially students.

“Students are in a unique situation because they depend on the university and their parents depend on the university to keep them safe, but it’s up to the individual to do things safely,” Watkins said. “The choices you make matter to keeping yourself safe in order for the university to work with you to stay safe, but it starts with you.”

For tips on how to prepare for an earthquake or other natural disaster, visit www.ddhs.mo.gov or call the C.E.R.T. alliance office at (573) 339-6799. To register for C.E.R.T. training at Southeast, visit www.semo.edu/training/cert.htm.