Editor's Note: *Names have been changed within the story to protect the identity of the sources and their families

In 2012, the Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), giving hope to children of undocumented immigrants across the United States for a better, more legal future. And, according to Southeast senior *Mary Smith, a future that does not require them to live in the shadows.

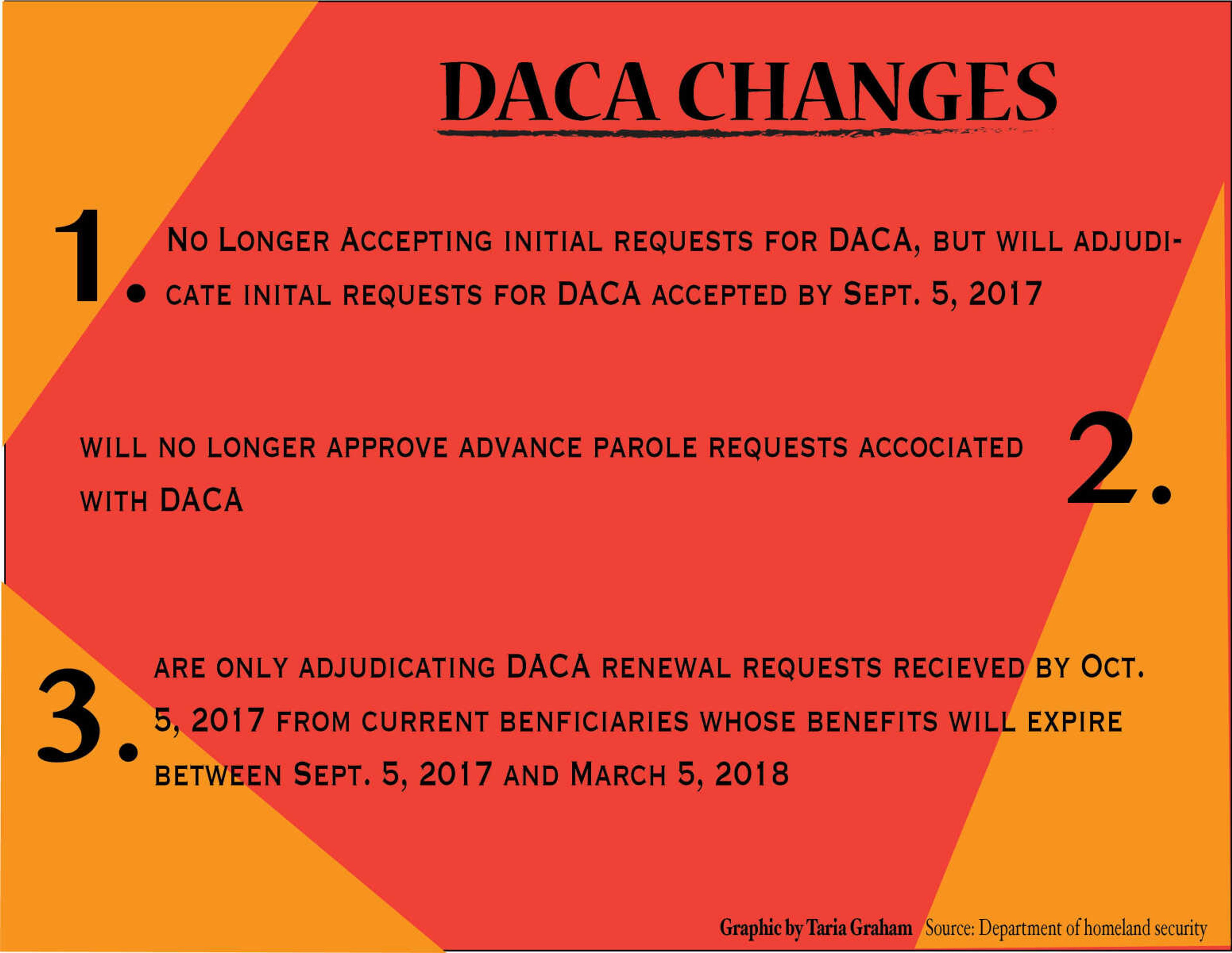

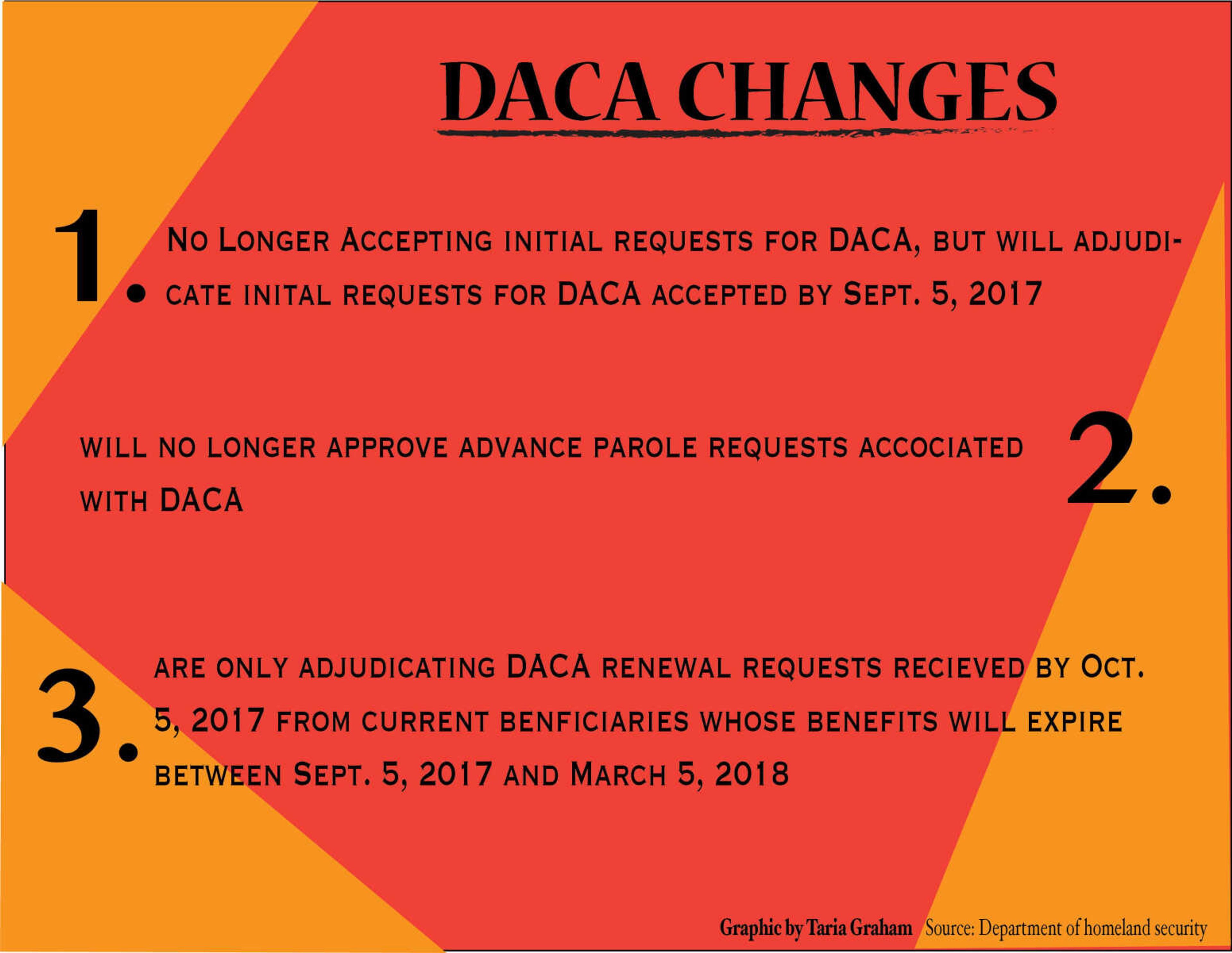

On Sept. 5, the Trump administration announced that the U.S. will no longer be accepting initial requests for DACA and initiated a phase out of the program, according to the Department of Homeland Security website.

There are more than 800,000 DACA recipients in the U.S. and 3,900 in Missouri alone. For these people, some of whom are currently enrolled at Southeast, their once-found hope has been turned into uncertainty about what their future may hold.

Former student Eduardo Gasca is a DACA recipient living in Cape Girardeau, the only town he’s ever known.

“I came to America when I was 1 year old,” Gasca said. “My family left because the area we were living in was very unsafe. They wanted me to have a better future.”

Smith said she was brought to America when she was 8 years old. Her mother had been searching for a job for a year,to no avail. She came to America to work on a farm in the Bootheel of Missouri.

“She did it for me — so she could provide for me and give me a better future,” Smith said. “My mom works so hard and always follows the law.”

When Smith began attending school in the U.S., she could not speak any English.

Both Smith and Gasca grew up in Missouri and went to public schools to get an education. The difference is, their parents are undocumented immigrants who crossed the border illegally.

It wasn’t until the end of her eighth grade year when Smith find out she was undocumented. She was looking into colleges to attend, but realized she did not have the proper information to start filling out paperwork.

Gasca said he had always known he was undocumented, his parents made it a point to stay out of trouble.

“I always knew I was undocumented, because I had to be careful,” Gasca said. “Once I got into junior high I really started to understand it and started looking into the laws and politics. I knew it wasn’t good.”

Before DACA, Gasca said college wasn’t even in the question. Attending college, getting a driver’s license and many other things required a Social Security number, something he simply did not have.

When DACA was announced, both their lives seemed to open up to the opportunity to follow their dreams.

__To receive DACA, undocumented minors had to fall under these guidelines:__

1. Were under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012

2. Came to the U.S. before their 16th birthday

3. Have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007

4. Were physically present in the United States on June 15, 2012, and at the time of making their request for consideration of deferred action with USCIS

5. Had no lawful status on June 25, 2012

6. Are currently in school, have graduated or obtained a general education development certificate, or were honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or Armed Forces of the United States

7. Have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, or three or more other misdemeanors and do not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety

(Source: The Office of Homeland Security)

Once approved to receive DACA, recipients gain two-year permit that must be renewed in order to keep documentation legal.

“I think the qualifications are great,” Gasca said. “If you don't put qualifications then anybody could just qualify and it wouldn't be people that shouldn't be here that are here. It's a great deal.”

DACA gave children the opportunity to go to college, get a driver’s license, work within the community and more.

All his life, Gasca wanted to be an entrepreneur.

He finally saw his chance to pursue his dreams when he was able to apply for DACA as a junior in high school.

Smith, who applied for DACA her senior year, saw it as a way to help out her mother. Smith said her mother risked everything coming to America for a better future, and she wants to be able to help her in every way possible. When Smith received her first permit through DACA, she applied for her driver's license so she could drive herself and her family around legally.

She also used it as an opportunity to go to college and get a degree so she can work a valuable job. DACA recipients may apply for FASFA, however they cannot receive any federally-funded financial aid. Most DACA recipients have to rely on merit-based scholarships and the FASFA report to prove they are eligible for endowed scholarships.

The main restrictions, according to Smith, are her rights to travel and her right to vote. DACA recipients cannot leave the U.S., and Smith has never left the state of Missouri.

She has not been back to Mexico since she left when she was 8 years old.

“We cannot vote. We abide by whatever other people are doing even though we are a part of society still. Your voice isn’t being heard,” Smith said. “Our voice is drowned out. Why even speak out if it’s not going to be heard?”

When the phasing out of DACA was announced, their hopeful future seemed stripped away with uncertainty about what’s next.

“I thought it was unfair,” Gasca said. “It wasn’t a broken system, it was working perfectly fine. Why trump everybody's future? The majority of DACA recipients are in the same positions as me, they don't know about their home countries and they don't know what it's like.”

Smith said her reaction came during the 2016 election when Donald Trump was voted into office.

“I cried all day,” said said. “How could they do that? Do the voters not know that they just signed off my sentence?”

*Sam Walker, a Southeast junior, is a first-generation Mexican-American whose parents are illegal immigrants who crossed the border when they were teenagers.

“With Obama, he was coaxing us out of the shadows, then Trump comes in and it’s like ‘Oh, nevermind,’” Walker said. “It’s basically them saying we don't want you to trust the government and want you to go back in the shadows.”

Walker said people do not understand the reality of being an immigrant. She has hidden her family’s undocumented status for her entire life.

“None of my friends know. I always protect my family. I don’t trust anyone with that information and I cannot take that risk of getting my parents deported,” Walker said.

DACA recipients across the board now have new stresses coming into their lives. As for Southeast DACA students, their priorities have switched around.

“I should be worried about getting a job once I graduate,” Smith said. “But now, I’m worried that’s not even a possibility. Am I going to even be here to graduate? Am I going to be deported tomorrow? Maybe next day? Are they going to go after my family?”

According to Smith, if DACA is completely removed, the former recipients won’t be able to get jobs within their education fields. They will have to apply for low-paying jobs where they do not have labor rights to protect them.

“When I got DACA I thought, ‘Now I can finally help my mom,’” Smith said. “And now I can't, I am a drawback to her.”