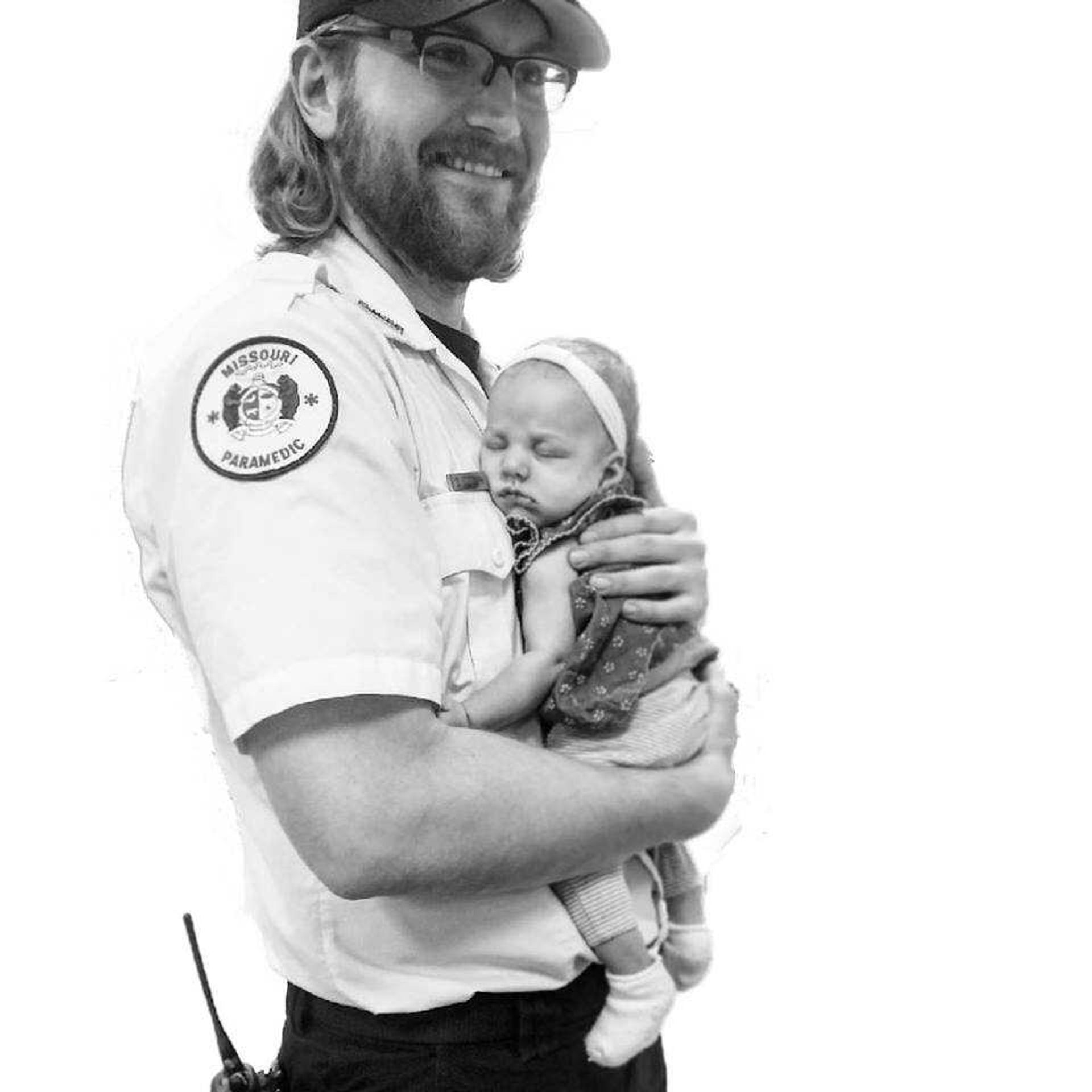

David Ludolph was working the night his brother died.

​

“I didn’t [respond to the call] thank God,” Ludolph said. “Someone else I was working with did.”

​

Ludolph is a paramedic for Cape County Private Ambulance and a former Southeast student. He said it was by chance he wasn’t sent to treat his brother.

​

“I recognized where it was,” he said. “I was assuming, and kind of freaking out, because really, it was supposed to be my call, and they accidentally messed up the rotation.”

​

He said his younger brother, Wade Ludolph, had been alienating himself in the months leading up to his fatal overdose in October 2017.

​

“I had suspected stuff was going on with him like that, like he was probably doing something again,” he said. “I probably hadn’t seen him in six months. Tried to, but hadn’t. Before going to bed it was running through my mind, like, ‘What if I end up having to run [a call] on my little brother.’”

​

David was with another patient when he received word of Wade’s death. David’s co-worker, who responded to the call, administered Narcan, a drug that reverses the effects of overdose. But too much time had passed.

​

“He was way past help, and they still tried to help him,” David said. “I saw him in the hospital, he was blue.”

​

David said his brother’s opioid use was a result of too-easily accessible prescription drugs, and possession charges that lingered, setting him up for failure.

​

“He got arrested and got caught with a bunch of different pills, bunch of heroin, went to jail, got out, was clean, was doing great, really really good,” he said.

​

But Wade’s felony charge made finding a meaningful job difficult and depression crept back in, with drug use close behind.

​

“You’re trying to shield how you feel and it builds up and builds up, so you keep doing the heroin to not deal with it,” David said. “So I think it prolongs the reasons why you’re feeling depressed. They do it to be numb and to forget.”

​

He said the charges associated with possession of opioids are doing more harm than good.

​

“There’s a difference between having a brick of heroin to sell to people, and being found with a little bit. The only person it's really affecting is the person doing it, and they need help, they don't need punishment. It makes it even harder for them to get out of where they’re at.”

​

Even without a car, Wade was able to access heroin and other substances in Cape Girardeau.

​

“I think it’s a really really hush, hush thing,” he said. “I think it’s ‘Well, this guy’s done heroin with me a couple times, I’ll see if he wants to buy some now.’”

​

But Wade’s addiction began much more traditionally.

​

“Really I don’t think heroin is where it starts; I think access to prescription opioids is where it starts,” he said. “I almost guarantee you he tried prescription opioids before heroin. It’s just the access to it; it’s crazy easy. The first time someone does an opioid it was prescribed to them.”

​

David truly believes that he and his family did all that they could to be there for Wade.

​

“He had all kinds of people trying to help him, all kinds of people, and I think it really comes down to the availability of help, I guess, and how much they want help,” he said.

Treating Opioid Overdose

Ludolph has been working as a paramedic for four years. He said he and his co-workers encounter fatal opioid overdose once a week on average.

​

For that reason, Narcan has become an indispensable resource. Ludolph said he ensures his ambulance is stocked with enough Narcan to treat several people each shift.

It can be administered intravenously or nasally, Ludolph said, depending on the condition of a patient’s veins.

​

“If they’re shooting up, their veins are probably terrible,” Ludolph said. “If their veins are in good shape, I’ll start it intravenously.”

​

Ludolph said in Cape Girardeau, calls related to opioids may mean responding to known users or to older adults having adverse effects to a new medication.

​

Heroin users, he said, are very rarely over 30. In Missouri, in 2016, 29 percent of heroin overdose deaths were between 25 and 34 years old.

​

Ludolph has four years under his belt as a paramedic, and said knowing how to avoid combativeness is a key to treating overdose.

​

Before treating an unresponsive patient with Narcan, he said he tries to rule out other possibilities, especially if illicit drug use is not obvious, but the signs are almost always the same.

​

“Pin-point eyeballs, they’re not reactive or unconscious, it’s probably some kind of opioid,” Ludolph said. “Low heart rate, low blood pressure, barely breathing; that’s probably what it is.”

​

He said administering Narcan is best done slowly and carefully because “slamming it” can cause a state of immediate withdrawal in opioid dependent patients, causing seizures and vomiting.

​

He begins with .5mg and works up to 2mg, while monitoring vital signs. If the patient shows no sign of improvement, another 2 mg is pushed slowly.

​

“Generally after that you can kind of tell that they are probably gone,” he said.

​

But when the treatment is effective, he must remain alert.

​

He said patients often grow combative after Narcan is administered, because the substance has effectively taken away their high. Working from inside his ambulance is where he feels most secure, and getting the patient to the hospital is a priority, but it often takes some convincing.

​

“Everyone responds differently to Narcan,” he said. “Some people, right then and there, start talking to you, some people are still confused for awhile. Another factor can be how close they were to being dead.”

​

He said users almost always lie about their drug use, even after being revived from overdose.

​

“People with addiction lie, and that’s just part of the disease, to protect the addiction basically,” he said.

​

He said his uniform, to a confused overdose survivor, resembles law enforcement, and makes it difficult to build trust with the patient.

​

“That’s another reason why we try to get them to the hospital,” he said. “Hospitals have more time and resources to gain their trust and treat them better.”

​

It is not uncommon to have to restrain overdose survivors, and if the patient is a known user, who is prone to violence, a police officer can sometimes ride along in the ambulance to the hospital.

​

He said when he began work as a paramedic, emotion and nervousness played a role in his treatment of patients.

​

“Now I’ve just done it for so long, I know that staying calm and the disconnect is important and you kind of push off how you feel until after the call,” he said. “Then it all kind of rushes in and you’re, like ‘OK, now you’re allowed to feel.’ Because to do your job, if you do it emotionally, you’re going to screw up, or you might forget to do something, because it kind of clouds your brain.”

​

He said clarity is imperative because of the risks associated with the job, including extremely potent synthetic drugs that can cause harm upon contact.

​

On Narcan, David said although it is saving lives, he believes it is, in a sense, fueling the fire of addiction.

​