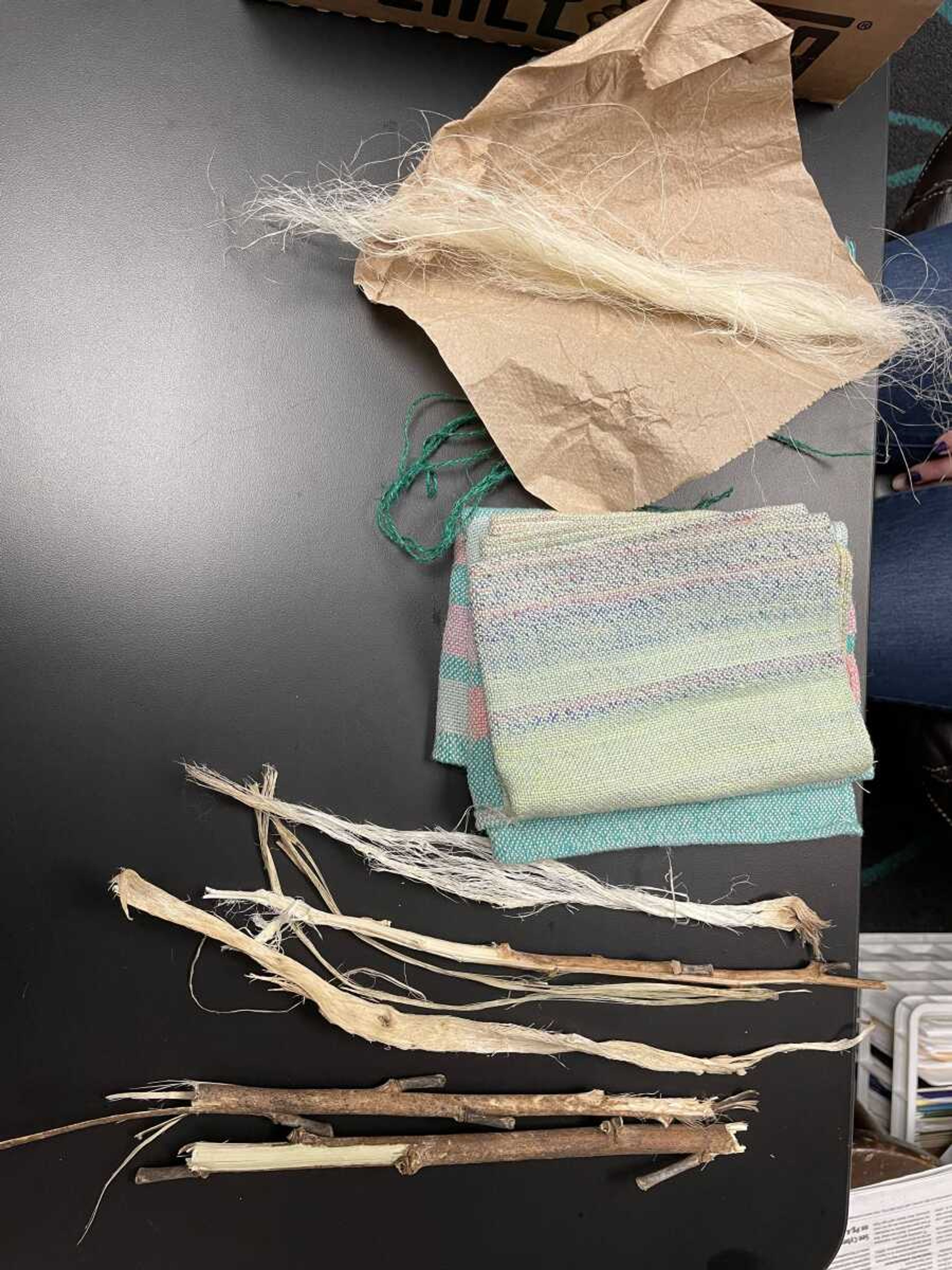

SEMO chemistry professors Rachel Morgan Theall, Sarah Shaner and Sajan Silwal submitted their abstracts to the American Chemistry Society (ACS) about using okra plants to remove waste from water and the environment and to create textiles. When Morgan Theall came across bast fibers, woody fibers obtained from flowering plants, similar to hemp and flax in the okra plant, she wanted to experiment with the “edible plant fiber.”

Morgan Theall began her experiment with okra at the beginning of 2020 at the Charles Hutson Horticulture Greenhouse in Cape Girardeau. She takes care of approximately 400 okra plants at the greenhouse. Morgan Theall said she began her experiment with okra to create textiles out of more environmentally-friendly fibers.

“We want to get away from cotton. [Cotton] is a natural fiber but takes a lot of water and pesticides to grow. We do have ways to pick it, but it's not environmentally-friendly, while hemp is more environmentally-friendly,” Morgan Theall said. “You get a lot of fiber from each plant, but [hemp] isn’t producing food. We [hope to] get something like okra that's producing food and get the fiber out of the plant.”

Morgan Theall said she wanted to experiment with a plant that does not use many natural resources and could be grown in drier climates of the world, as well as a plant with fibers that could be used to create building material. She said okra does not need a lot of water and will grow in the drier parts of Africa.

“The lack of water [in Africa] is a huge problem. If you could figure out how to use the parts of the okra plant [for] building materials in places where they have access to little water, it would be hugely changing for the people who live there,” Morgan Theall said.

In the future, she wants to map out the cross-sectioning of the okra plant. With the pictures, she will identify how fast the plant grows, how much cellulose the plant has and where to get the best fibers from the plant.

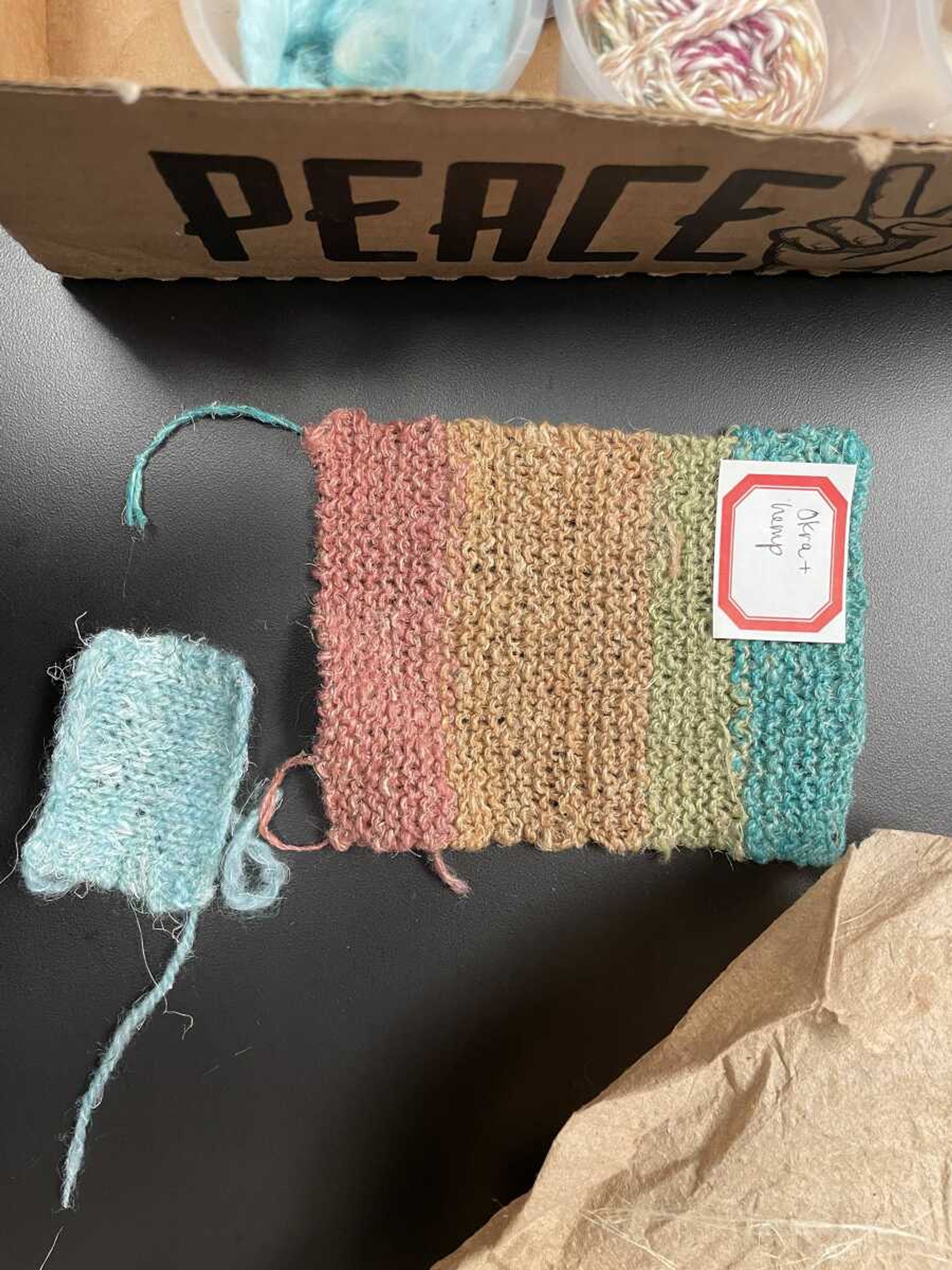

To create textiles, Morgan Theall first strips off the okra plant to tear it apart and uses a card to remove its sliminess. Next, she spends time cleaning the plant or leaving it in the field with enzymes to let non-bast fibers of the plant rot away. Then, she scrapes off any part of the plant that is not fiber and begins to process the fibers with bleach. After bleaching, Morgan Theall begins the dyeing process. She uses soda ash to make the okra plant slightly basic, stripping off hydrogens from the cellulose, and then uses T-shirt dye for the okra fibers to dye the fibers. To begin the weaving process, she either uses spindles or twists the fibers to hold shape.

“The twist allows the fibers to catch on each other and not pull apart, strengthening it. So, you twist [the fibers] in one direction, fold it in half, and [the fibers] will twist the other way to sort of ‘untwist,’ adding more strength,” Morgan Theall said.

Morgan Theall’s goal with the okra plants is to remove dyes and metals and adjust the pH levels of environmental contaminants in water. She’s interested in creating fabrics to potentially clean up industrial waste from fast-fashion industries. Morgan Theall said she describes her textile-producing process as slow fashion.

“There's fast fashion where machines [make the products] and people are the running machines. You buy a T-shirt for five dollars at Walmart, [the T-shirt] doesn't last for very long, and then you just toss it out, creating a lot of waste,” Morgan Theall said.

The American Chemical Society is a nonprofit organization for students interested in pursuing further education in chemistry. Students and professors are encouraged to submit their abstracts every year for the ACS meeting. Morgan Theall, Shaner and Silwal will present their research at the Fall 2022 ACS meeting in August.

For more information on the ACS, visit their website.