Attending and affording college has never been easy, but in 2024, students face many unique economic challenges and hardships. When adjusted for inflation, the 2024 federal minimum wage is about 40 percent lower than the minimum wage in 1970, according to statista.com. Additionally, the inflation rate, which the Federal Reserve seeks to keep at or below 2 percent, peaked at 8% in 2022, according to the US Inflation Calculator and federalreserve.gov.

SEMO students have it easier than some—Missouri has the sixth-lowest cost of living in the United States, according to the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center’s research; however, the challenge is still difficult for many and overwhelming for some.

How Much Does SEMO Cost?

In the 2023-24 school year, it costs an in-person domestic student $9,495 for tuition and $20,320 when factoring in costs for housing, a meal plan and supplies, according to the SEMO website. To put this figure into context, someone working full-time and making Missouri’s minimum wage — 12.30 an hour— only makes about $22,100 per year after taxes. Most students receive some form of scholarship to help offset this cost; however, it is still a huge burden, with the average student loan repayment plan lasting 20 years, according to educationdata.org.

The national cost of a public out-of-state tuition is $23,630, and the average cost of a public out-of-state tuition is $10,662. As of 2023, in-state and out-of-state tuition at SEMO are the same—$9,495 for the ‘23-’24 school year—and because of this, SEMO is cheaper than the national average for both in- and out-of-state students.

SEMO Students Share Their Story

Sophomore Wildlife Conservation major Madelyn Pyrtle lives and breathes by her calendar. She plans her days out months in advance; a typical day in her life involves precisely-planned trips to and from home in order to make it to class, access on-campus resources such as the computer lab, and work her shifts as a lifeguard at the Student Recreation Center.

One thing going wrong—like forgetting to pack her lunch—can ruin an entire day, but even on the best days, Pyrtle’s life is too hectic for her to keep up with.

“I pull a lot of all-nighters,” Pyrtle said. “I’m always tired. Oh, my goodness. I do not sleep a lot during the semester because I’m ‘go, go go go going,’ and when I’m not going, and I have a chance to rest, it’s usually spent somewhere that’s not really my home.”

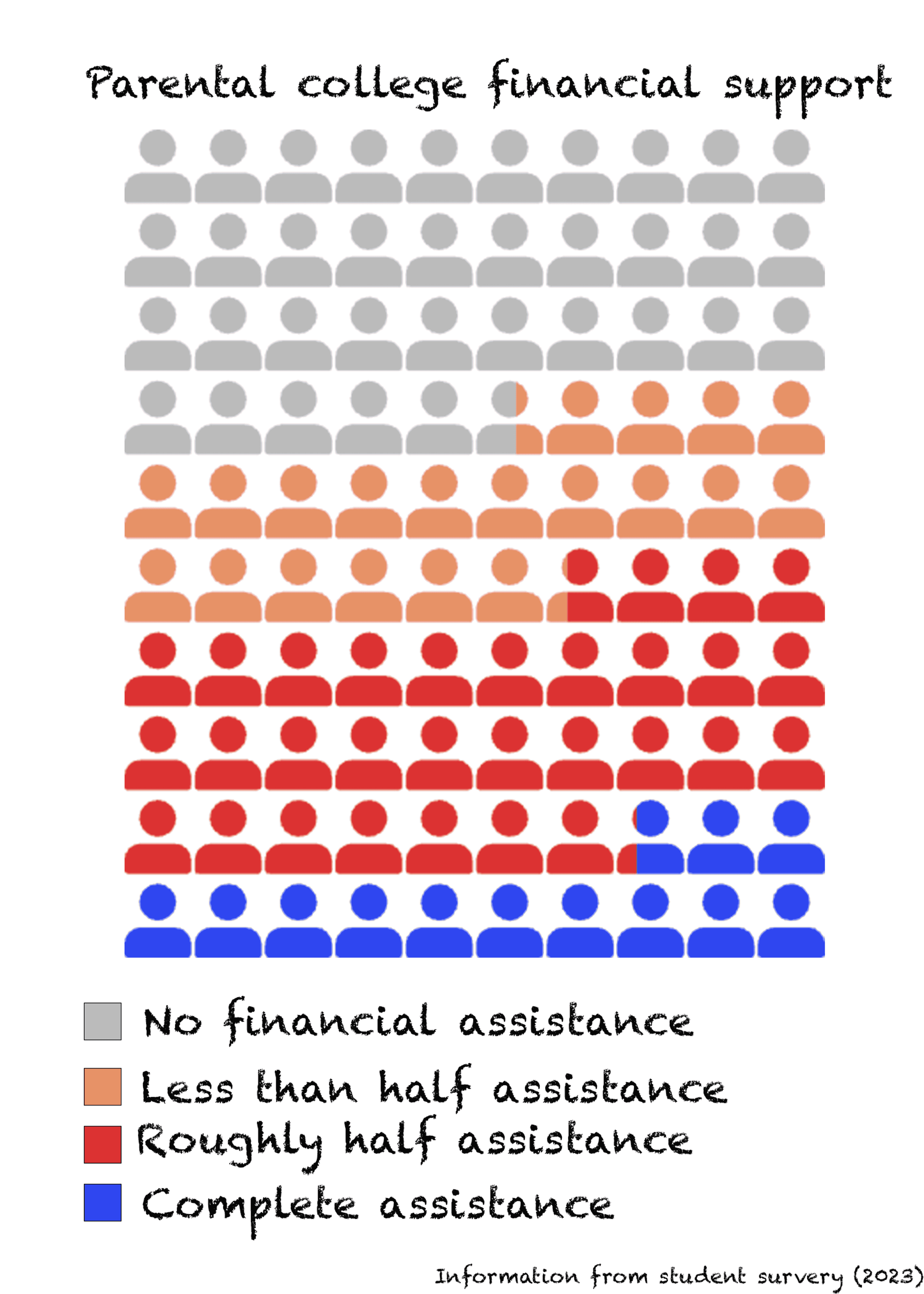

Although not all students’ lives are not as busy as Pyrtle’s, many still struggle with taking care of their basic needs, both physical and emotional. According to a survey of 89 SEMO students distributed through mass email and in person, 36 percent of students said their living situation negatively affects their education either sometimes or often. Additionally, 18 percent of students said their living situation was occasionally unstable to very unstable.

Meeting Basic Needs Before Students Can Thrive

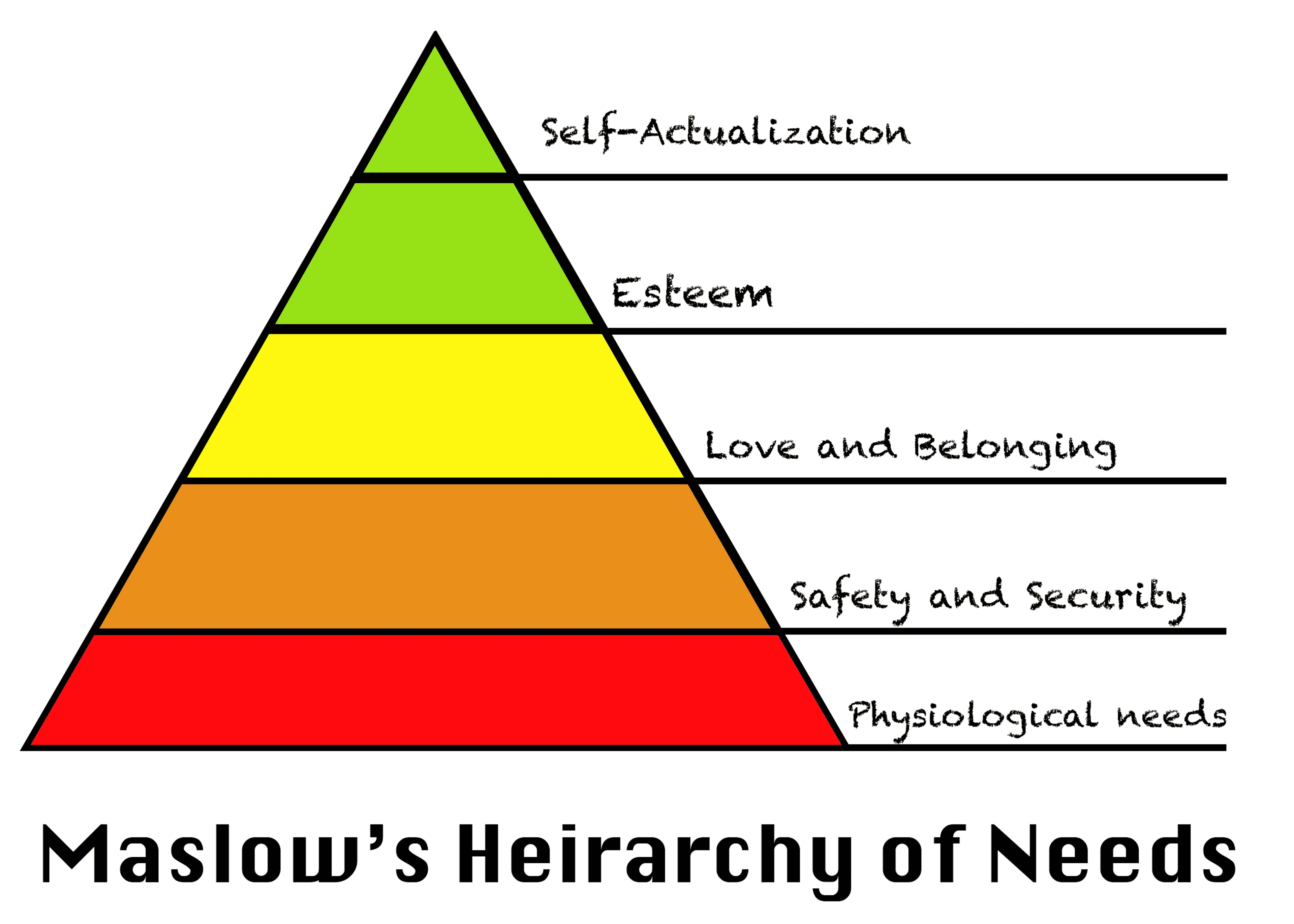

According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a concept developed by psychologist Abraham Maslow, humans must fulfill their basic needs, such as food, shelter, and safety, and psychological needs, such as having close relationships and feeling accomplished, before they can reach their full potential. In theory, a college is a place where students can begin the journey to self-actualization. But if their basic needs aren’t being met, according to this theory, it is very difficult for self-actualization, growth and accomplishment to happen.

The history of financial aid in Missouri has been relatively consistent over time, even before Missouri became its own state. History and Anthropology professor Courtney Kisat said historically, each county had what was called a “poor house” to help those in need, and available aid greatly varied.

Today, Missouri citizens must still apply locally for things like food assistance and financial aid. The amount of available resources still varies significantly county-to-county, so people in financial need getting adequate aid is, at some level, left to chance.

These trends continue at the college level: like Pyrtle, many SEMO students struggle to keep up with the demands of paying for college, taking care of their personal needs, and going to school. Sophomore historic preservation major Bailee Porteous needs to work two jobs in order to keep up with tuition and living expenses, and is often overwhelmed by their workload.

“I’m more focused on paying for college instead of learning at the college that I’m paying for,” Porteous said. “If I was financially stable, I wouldn’t have to worry about if my car broke down, or what if I get in a medical emergency? I have so many concerns that are kind of overbearing and take away from my academics; if I didn’t have to worry about any of that, I would probably be a straight-A student.”

Meeting Longer-Term Needs

Even if students' immediate needs are being met, many students are still not financially comfortable, and constantly must deal with the stress of living paycheck-to-paycheck. Senior exercise science major Shamus Landry is able to make ends meet, but almost always accumulates some credit card bills throughout the month, and has the looming threat of student loans to think about after he graduates.

Student loans are another complicating factor to add to Maslow’s equation. For many students, there is a mental disconnect between taking out loans and the reality of paying them off; according to Kissat, young people aren’t usually the best equipped to make large financial decisions.

“There’s a lot of hidden costs that students don’t really understand, especially if they’re taking out student loans,” Kissat said. “Young people who may not have a lot of financial literacy [are] making lifelong financial decisions without necessarily having the background, expertise or support to understand that.”

Many students wish there were more on-campus opportunities with more pay. Landry said in his experience, it can be hard to find an on-campus job, and many of the student workers he’s talked to said a raise would be extremely helpful.

Despite their shortcomings, there are many positives to on-campus employment. Junior health sciences major Sanaa Lewis works as a student worker in the Scully building, a peer advisor, and an orientation leader for the new student program. Her jobs, in addition to the scholarships she’s receiving, allow her financial stability, and she enjoys the interpersonal skills her jobs are teaching her.

“Working on campus, I’m able to learn different things that can help me in the future or help me work better with people, [and] I’m always willing to learn more,” Lewis said.

Sophomore nursing major Layne Collier also works on campus, and said although many students have a perception that on-campus jobs are exploitative and don’t pay enough, he feels that he makes a fair wage at 13.30 an hour.

“I think SEMO is one of the most generous colleges in the area,” Collier said, “when it comes to giving scholarships to students. Especially now that we’re test-optional, they made it more flexible and a lot easier for students to come in with financial aid that may otherwise not have gotten in if they went to another university.”

Aid Available at SEMO

It’s helpful for students to know their financial options in order to decrease and mitigate student loans. Collier said he wishes there was a clearer layout of how financial aid packages are divided, and where the money comes from.

“Endowed scholarships, in my opinion, are some of the easiest ones to get from SEMO. But a lot of the time, there’s not very clear direction about how to get those, or how they are divided up along the semesters,” Collier said.

Student Financial Services (SFS) is a starting point for students who need these services. SFS Director Matthew Kearney describes this service as a ‘one stop shop,’ where students can receive help with financial aid, and who also invoices students and handles billing.

“[We] try to get the math to work to where a student’s comfortable with coming here, paying their bills, being able to stay enrolled and meeting all their other needs as far as housing and food,” Kearny said.

SFS also directs students to other offices such as the Dean of Students, the Vice President of Enrollment Management, Residence Life, the food pantry, the Registrar's Office (if a student needs to withdraw or step away), and the Counseling Center.

There is also a small emergency fund that comes from SEMO’s United Way campaign, which provides several students a year up to $500 for emergency expenses.

“When you think about, you know, 10,000 students, it’s huge for that one or two students—it means everything to them to be able to stay in school and work through the issues that they have. But if you were to take a big picture look at the number of students we serve, it’s a pretty small number that are coming to us [for emergency needs],” Kearney said.

Non-SEMO Scholarships

Pell grants are a need-based federal financial aid option that students can apply for after completing a Free Application for Financial Student Aid (FAFSA). A student can receive a maximum of $7,395 for the ‘23-’24 school year, and the amount a student receives depends on several factors, including the student’s Expected Family Contribution, the cost of school attendance and if the student is full- or part-time, according to information from studentaid.gov.

Another popular form of scholarship for Missouri students is the A+ program. If a student attends a school with an A+ program, meets several grade- and attendance-based requirements and performs at least 50 hours of tutoring or mentoring prior to graduation, the scholarship will reimburse any unpaid tuition and fees at a maximum rate of $209 per credit hour, according to the Missouri Department of Higher Education and Workforce Development.

While these scholarships don’t fix everything, they can make a world of difference to those in financial need, and help pave the way for a better future.