It was P.O. Box 31.

Rodney Wilson was sitting in his Myers Hall dorm room in 1989 when he saw an advertisement in the then-Capaha Arrow for the Gay and Lesbian Student Association. He decided to write to the given address about something he’d been feeling since he was 7 years old.

Wilson grew up in Potosi, Missouri, with today’s population totaling around 2,500. He went to school with the same classmates year in and year out for 13 years, but he knew, even then, there was something “different” about him.

He was gay.

“At the time, things were much more difficult than they are today, and I knew this was unacceptable, I knew this would be disappointing, I knew that it went against the religious beliefs of the community, so I kept that information to myself from age 7 until I was at Southeast [Missouri State University] when I started the coming out process,” Wilson said. “So I held onto that information for a long time, but the need to accept it internally, and then to be truthful about it, gradually grew.”

Wilson studied at Mineral Area College for two years prior to attending Southeast. He said today, there are some four-year universities that offer degree programs through Mineral Area College, but at the time, he had to transfer to obtain his intended Bachelor of Science in secondary social studies education.

“To be a teacher I had to go somewhere, and Southeast was the place that seemed like the natural next step,” Wilson said. “In fact, I did not consider going anywhere else, that was where I would go.”

Wilson said Cape Girardeau isn’t a big city, but it is a big town. Coming from Potosi, it seemed “cosmopolitan.”

He had three different roommates from Japan during his tenure at Southeast simply because he wanted to.

“I wanted to meet people who were raised 10,000 miles away, who had a different outlook, a different culture, a different language, different religion,” Wilson said.

He tried Chinese food for the first time. His seven-day meal plan didn’t include Sunday evenings, so it became a tradition for him and friends to get together at Chan’s Restaurant on Kingshighway as a way to unwind before the start of a new week.

__Coming Out__

He learned to be more open about who he was. He mustered up the confidence to write to Southeast’s GLSA in April 1989 — that was step one.

Still, it was scary finally speaking up about something he’d been quiet about for well over a decade. Wilson said he drove from Myers to the post office and sat in his car in the parking lot to write that letter.

“I was afraid if I wrote it in my dorm room and then drove there, what if I were killed in the meantime? Well, someone would find the letter and then the secret would be out,” Wilson said. “So the fear and paranoia that I had and that many gay people had then, and some gay people still have today, I’m sure, even though things are so much better, the fear was profound and paralyzing.”

He initially met the adviser of the group, Dr. Carl Train, at a Chinese restaurant inside West Park Mall. Not until afterwards did organization president Johnda Boyce agree to be introduced.

“We were scared, we thought it might be a setup,” Boyce said. “We had this weird, cryptic, one-page letter to our P.O. Box, and we’re like, ‘I don’t think it’s safe to go meet this guy. I don’t know what this is.’ We were always under threat, of course, because of [naysayers] who were anti-gay.”

Wilson noted coming out was a process. Voicing his sexuality once didn’t magically make things any easier, especially in the 1990s. He said close friends and parents are typically the first ones told, but it’s another decision every new job, every new acquaintance.

“If you think about too, though, we all come out,” Wilson said. “We come out as straight or gay all the time. If a person is heterosexual, they get a new job and someone says, ‘Are you married?’ and a heterosexual man would say, ‘Yes, my wife is named Karen,’ that’s coming out. It’s just we don’t think of that as coming out because heterosexuality is the norm.”

He said he was lucky in that most of his friends and family were supportive. Some took more time than others to grow accepting, but he’s not begrudging.

“I think that’s fair, because it took me, for example, several years to process this information,” Wilson said. “I can’t expect that everyone will process it in two days. You have to give people time.”

He said while his mother understood within a matter of 24 hours, it took his father closer to two months.

“She said, in fact, that she had known for many years,” Wilson said. “In fact, when I said, ‘I’m gay,’ her first words out of her mouth were, ‘Son, I’ve known for years.’”

__Balancing Faith and Self__

There’s a religious aspect to coming out, too. Wilson remembered waking up on Sunday mornings to watch Jerry Falwell’s “Old Time Gospel Hour.”

“A gay person has to come out to God, in a sense,” Wilson said. “Not that God already wouldn’t know, obviously. Theologically God knows, but a LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender] person, if they are a religious person or have a religious background, they have to also wrap their head around, and probably better put, wrap their heart around the fact that they are gay and their religion might not approve of that.”

Wilson said GLSA mostly acted as a support system. For instance, the group drove up to St. Louis his senior year in the spring of 1990 to see the LGBT-themed play “Some of My Best Friends Are…” by Joan Lipkin, producing artistic director of That Uppity Theatre Company.

“It was comfortable to be at a barbecue with 10 or 12 other students who had a very similar experience to your own,” Wilson said. “‘This is very comfortable,’ and it was the first time ever to experience that.”

Wilson said they did advocate for acceptance, but they also knew it would take more than a handful of college students to influence radical change. They were told they were criminals under Missouri law when they requested fair treatment, according to Boyce. She said laws citing sexual misconduct were used as means for discrimination.

“We would have never thought in 1989 to advocate for equal marriage rights, that would not have crossed our minds as a possibility of something that would ever happen,” Wilson said.

__Growth Through Struggle__

GLSA had only been on campus for no more than four years, and students weren’t used to its recognition. Boyce said people were stuck with a belief that they didn’t and would never know anyone who identified as gay.

“It was unusual for many of the students even, all of us coming from rural, conservative southeast Missouri, many of us having a religious background, so it was unusual to suddenly be confronted with the idea that there are LGBT people… and they’re now saying they want to be recognized, they want equal rights, they want equal access,” Wilson said.

He said GLSA would continue to hold Blue Jeans Day each spring, where wearing blue jeans represented a person’s backing for gay rights.

“Now everyone had to think about, ‘Well, I wear blue jeans every day. It’s not summer yet. Am I going to wear blue jeans or am I going to intentionally choose to wear something else because I don’t want to, in any way, appear to be supporting lesbian and gay issues?’” Wilson said.

People would walk around campus wearing pajama bottoms, more often than not.

But it wasn’t all bad. Boyce said Student Government Association allotted them the second-highest amount of funding for a student organization because of the programs they brought to the campus life. The Dean of Students Office provided GLSA a space to run what they called the Prideline as well, an answering machine to notify the Southeast community of any organization-specific news or events.

Former dean of students Thomas Lovett would stop sophomore Boyce on her way into the office and ask her what seemed to be a simple question — “Johnda, how are we doing?”

“What he meant, because he told me this more than once, is that he felt like how gay and lesbian students at Southeast were being treated was a sign of how we revolved as a university,” Boyce said. “He said, ‘We’ll be a real university when things like gay and lesbian students being treated well happens here.’ He believed that was the hallmark of a real university, and we were on the cusp of becoming a real university and that I could tell him how we’re doing on that track.”

__An Idea Evolves__

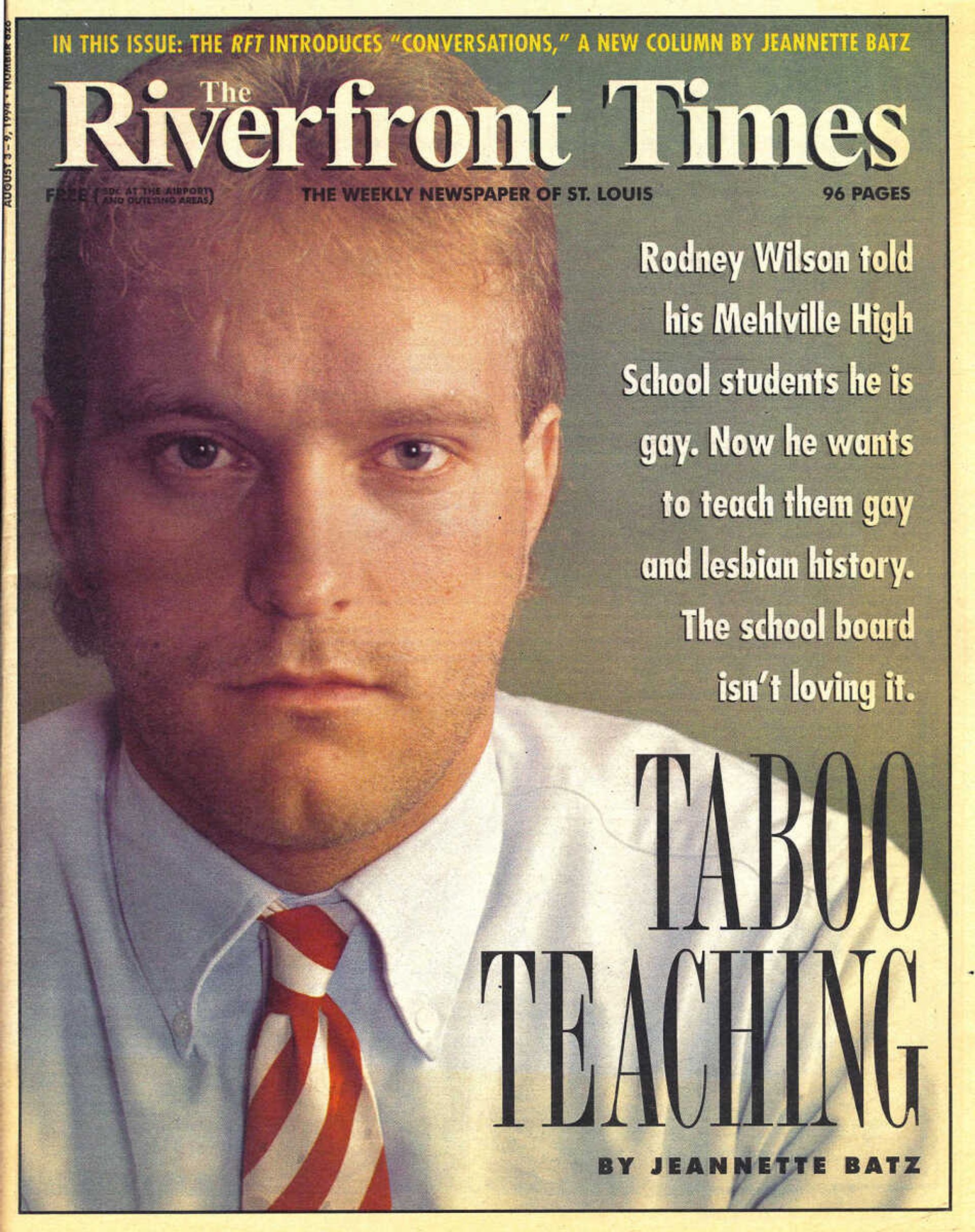

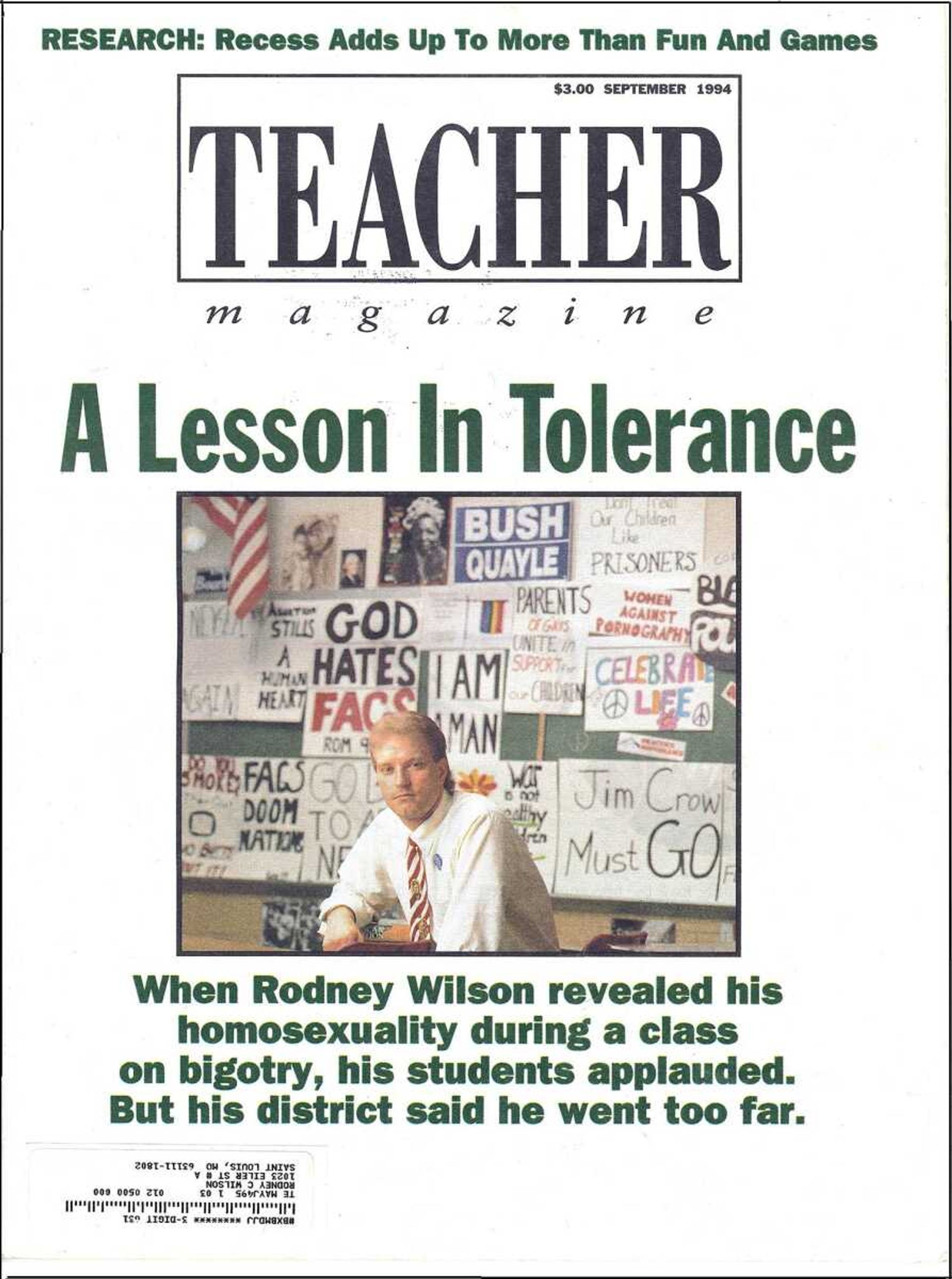

Wilson had a scholarship to complete a master’s degree in history at Southeast and work as a teacher’s assistant, but his plans changed when he was offered a position at Mehlville High School. He opted for the job to help in paying off his student loans, instead, and taught social studies, American history and world history there for the next seven years.

In January 1994, Wilson proposed Gay and Lesbian History Month, later to be titled LGBT History Month, for the first annual celebration that October.

He anticipated his appearance in the media, and he wanted to have some say in what would be leaked. As a result, he became the first openly gay K-12 teacher in Missouri.

“Back then, openly gay teachers in K-12 public schools were rare, and in Missouri and other more conservative states, they were unheard of,” Wilson said.

He had a poster hanging on his classroom wall he had just returned with from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., the week before. During a discussion about World War II, he highlighted that the Nazis persecuted more than the Jewish community.

“It had the various different patches that people would have to wear in the prison camps, including the Star of David, of course, and it also had a pink triangle, which is what an inmate who was there for being gay would wear,” Wilson said. “So I did say to my students that if I had lived then, I would have to wear this pink triangle, because I wanted them to understand that all sorts of people were affected and that we had to therefore be vigilant about persecution of any group.”

Wilson said as a high school teacher he was up for tenure in his fifth year, and March 1994 was only his fourth. He put his career on the line, but he stayed at Mehlville, was granted tenure and taught there two additional years following.

“I left the school when I was ready to leave, when I was ready for the next chapter of my life,” Wilson said.

So his idea for LGBT History Month took off. He sent it out to any and every LGBT organization he could find an address for. National organizations filed endorsements. Within the first year, the governors of Oregon, Connecticut and Massachusetts issued proclamations for October to adopt the celebration. Cities in Missouri like St. Louis and Kansas City did the same the next year. Now in its 22nd year this October, LGBT History Month has spread primarily throughout colleges and universities across the country.

Wilson was inspired by other observances like Black History Month in February and Women’s History Month in March.

“When I was teaching history in high school and I noticed in my textbook, for example, there was 800 pages and there was no mention anywhere of anything about a gay civil rights movement or an LGBT person — nothing — I decided that I wanted for LGBT individuals something like Black History Month,” Wilson said.

Black History Month was started by Carter Woodson as Negro History Week in 1926 to publicize and honor the history of African Americans. Wilson led his commemoration under these same concepts.

“I also believed and [still] believe that it’s very good for people to know their own history,” Wilson said. “I know that learning LGBT history helped me, and I think then it would help other people too, gay and non-gay.”

“We need to know that there were heroes and heroines and that there were people who made big contributions to society throughout the decades and centuries that were gay or bi or trans,” Boyce said. “We needed to know that we, too, could achieve things that would be of broader interest than within the gay community. We could make contributions to the greater society and do that even living as an oppressed minority.”

While in the planning stages, Wilson said he carried on his master’s degree at the University of Missouri-St. Louis along with his full-time employment at Mehlville. He founded the St. Louis branch of the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, shortened as GLSEN, then too.

Wilson, with the help of University of Missouri-St. Louis history professor Dr. Gerda Ray, as well as other graduate students in history, organized a film festival through October for LGBT History Month’s first year.

Controversy struck up again in 1995 when the National Education Association passed a resolution supporting the celebration. Due to increased resistance from opposing groups, the NEA voted to eliminate all exclusive indications of any history month by 1996.

Wilson moved to Massachusetts in 1997 where he worked at a house of correction teaching inmates between the ages of 17 and 21, math, reading and writing. He also tutored English to Spanish speakers, instructed GED classes and managed an Adult Basic Education (ABE) program at a community college. He didn’t move back to Missouri until 2011.

__Looking Forward__

He finished a second master’s degree in 2012, concentrating in religion this time around. Nonetheless, Wilson has taken on projects outside of the classroom, including working with his partner Dan Steadman, writer and director of independent local film “Love Chronicles (of the Cape).”

His chief focus, though, is on his students, beginning just where he did, at Mineral Area College. There, he teaches courses in American political systems and comparative religion.

As for Boyce and Wilson, they’ve stayed good friends. Boyce acted as the secretary for LGBT History Month’s coordinating council.

But she explained Wilson’s hopes for equality spanned broader than the LGBT community, even from the start.

“Here’s this white guy passionate about Women’s History Month, here’s this white guy who knows his African American History better than anybody I’d ever met and really passionate about it, too,” Boyce said. “Basically, here was a guy who didn’t have to, it wasn’t his community, but cared a lot about African American history, women’s history, civil rights issues, Native Americans, Latinos and Latinas, he just really cared about marginalized groups, always has cared about marginalized groups.”

In regards to today’s young people struggling to express their sexuality, Wilson referenced the It Gets Better Project:

“Not only does society get better by becoming more warm and inviting of all kinds of people, it gets better personally as you gain confidence in yourself and as you find and gather friends who are on your side,” Wilson said. “I think that would be the message, that it does get better, it is OK to be different, we’re all the same really, deep down, and that one should take it a day at a time. There will be ups and there will be downs, but the ups will far outnumber the downs.”