Clarification: The story has been edited to better reflect the views shown in the article.

On Feb. 15, 1994, SEMO student Michael Davis was pronounced dead from internal bleeding, after suffering from “fractured ribs, lung, liver and kidney damage, a bruised and bleeding heart, and spinal hemorrhaging.”

In a story published by AP News, Davis’s mother described him as a kind soul who “couldn’t kill a spider,” and the hazing as “cold-blooded murder.”

Davis was pledging to Kappa Alpha Psi. More than a dozen men associated with the fraternity were prosecuted, and seven were charged with involuntary manslaughter. The fraternity was banned from campus.

The Southeast Missourian reports that after this incident, hazing was scrutinized nation-wide, and legislation was passed in Missouri to make serious hazing a felony.

In February of 2007, Zeta Phi Beta members Darleta McKennis-Weems, Ashley Moore and Jessica Reynolds forced a student to eat garbage, hit her and sprayed an unknown substance in her face.

These three women faced up to a year in jail with the charges of third-degree assault and hazing. All three women pled guilty and were charged with two years of probation due to a judge's suspension of the original jail time.

The SEMO Zeta Phi Beta chapter was started in 1994 and is still active on campus today.

What really is hazing?

The instances of hazing accounted above are some of the more extreme examples. But considering the fact that according to stophazing.org, 55% of college students involved with clubs, teams and organizations experience hazing, there seems to be a lack of clear information among students about what exactly hazing is, how acceptable it is and how it should be dealt with.

Vice president of student and campus life Bruce Skinner said hazing is anything current members of an organization make a potential new member do that exerts power over them.

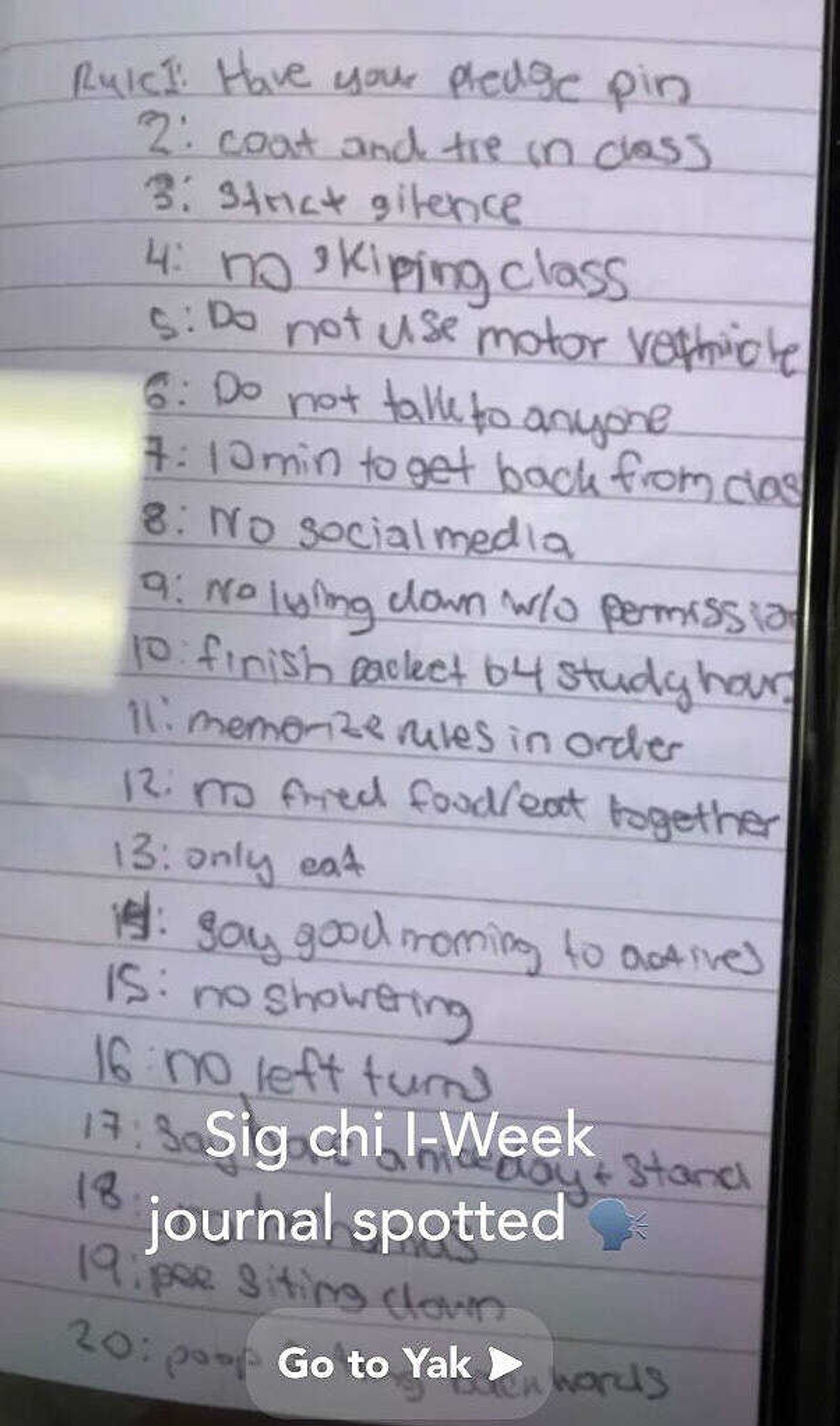

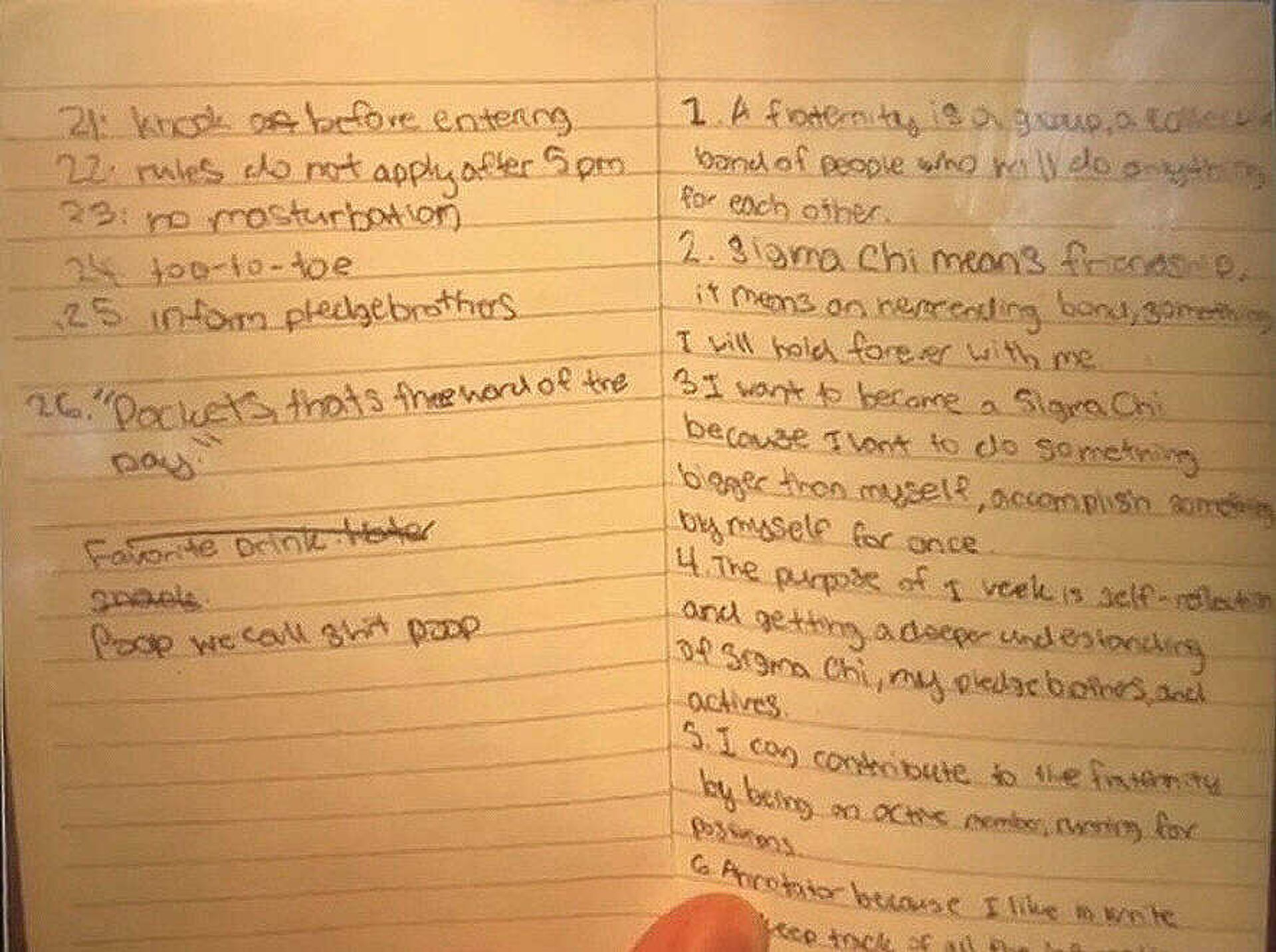

Skinner said things like physically putting your hands on someone or denying them food or sleep are considered hazing. However, not all cases are as clear-cut, like making new members of a fraternity wear a suit and tie around campus.

“What I always say to chapters is, ‘What is the purpose of that?’ If the purpose is to demonstrate you have control over them, yes, you’re hazing them. If it’s to have your new members understand that they aspire to be more than just a frat guy, but to be a fraternity gentleman, so long as that’s part of it, then no, you’re not hazing,” Skinner said.

According to Skinner, hazing happens in many different groups, from the military to marching bands to athletic teams.

“Hazing isn’t [exclusively] a Greek problem; it is an organizational problem,” Skinner said. “It won’t take you long to find examples of hazing in the military. There’s a couple examples where when you get your wings, they're punched on your chest, and they’re driven into your skin.”

Skinner describes hazing as what people in organizations believe they have to do to make new members demonstrate they want to join badly enough or are good enough to join.

Jeremy Heider, psychology and counseling professor at Southeast, said this phenomenon is described as “effort justification.”

“It’s a classic persuasion technique. If you want more commitment from members on the back end, make it more difficult to get it. It’s a pretty linear function — if it’s kind of hard to get in, then they’ll kind of value it more than other things in their life. If it’s really hard to get in, they’ll probably really value it more than other things in their life,” Heider said.

A common result of effort justification is cognitive dissonance, Heider said. If someone gained membership to a group that involved hazing and stopped enjoying being a part of the group, their brain would be hesitant to leave in an effort to justify how hard it was to get in.

“Most people want to avoid that mental quandary of, ‘Wow, I got tortured for weeks, for what, nothing?’” Heider said.

A pledge’s personal experience with hazing

Former SEMO student Samuel Hillig started his first semester at Southeast Missouri State University in the fall of 2021, hoping to join Greek Life and be involved with a fraternity.

Hillig described a mostly positive experience for the majority of his pledge process to Phi Delta Theta and mentioned requirements he called “fun.”

“We did signatures or ‘sigs,’ and basically, you’d have a book, and you’d go around, and you’d have to meet so many members of the fraternity in a week and write down personal things about them,” Hillig said. “They’d also quiz you on some of the questions.”

As the weeks developed and Hillig became more involved with the fraternity, he made it to the last week of the initiation process, which the fraternity called “Pledge Week.”

Hillig described an event where pledges were picked up in a car and then blindfolded. During the car ride, they were instructed to sing, forced to listen to extremely loud music and yelled at. The driver would also often swerve the car to the left and right.

He said the pledges were then dropped off at Trail of Tears State Park and were instructed to get out of the car blindfolded and put in front of a campfire.

They were then instructed to answer questions one by one about either the fraternity or its members.

For the next activity, Phi Delta active members tied Hillig and two other pledges together. Hillig was only allowed to see, the second member was only allowed to hear, and the third member was only allowed to speak.

Together, they had to walk down a trail and find a Phi Delta handbook along the pathway. After they completed this task, Hillig said they were finally taken to the final area of the event.

“Then they had us march up [a hill] in a single straight line, like a chain gang,” Hillig said. “At the top of the hill, they lined you up, and then they tell you to take your blindfold off. They turned us around, and they’d have a person behind you. That person behind you was your pledge father.”

Hillig said despite the hazing he endured, it was still mostly a positive experience. He also said just because it was personally manageable for him does not mean it would be a comfortable or easy experience for everyone.

“I could see how you could get scared or nervous or anxious very quickly,” Hillig said.

On top of trying to pledge to Phi Delta, Hillig was also trying to balance school. He said personally, he could not balance both due to the amount of tasks, events and requirements pledges had to complete.

Other views on hazing

Skinner said the way people perceive and understand hazing has been changing.

“The definition of hazing is more widely accepted than just physically putting hands on people. We make all students that join the Greek system here sign what we call the white card, and it specifically says that hazing is not accepted under both the University and the organization standards, and you cannot agree to be hazed,” Skinner said. “Under Missouri law, you can’t agree to be hazed.”

What can be done about hazing

Vice president of risk management for the Interfraternity Council Harry Meyer agrees with Skinner’s definition of hazing, and said there are two different types of hazing: mental and physical.

“Really, what hazing is, is being forced to do something that you don’t want to do or wouldn’t normally be doing,” Meyer said.

To bring awareness to the specifics of hazing and how to avoid it, Meyer is helping plan the University’s Anti-Hazing Week, which takes place Sept. 19 to Sept. 22. During this weeklong event, there will be a candlelight ceremony in front of Kent library, guest speakers who have lost loved ones to hazing and more.

“With our Anti-Hazing Week, we hope to bring that to light to show that there isn’t just one form of hazing. If you’re going through something, please reach out and inform the Greek Life Office,” Meyer said. “Hazing has no place here in Southeast Greek Life.”

If you or someone you know would like to report hazing, visit the SEMO website.